The pair of dark, brooding, jungle paintings hung amidst the bright, airy watercolors of Wisconsin farm scenes. Layered with thick strokes of hunter green and burnt umber, the canvases dangled from S-hooks on a pegboard wall in our family’s dusty basement. My father’s art studio was in the small storage shed on the other side of that basement wall, and he’d retreat there after supper to do freelance sign-painting jobs or just to escape the chaos of 3 young kids running around a modest 1000-square-foot Chicago flat. Sometimes he’d bring me downstairs with him to work on art projects as he patiently groomed me to be an artist just like he was. Coupled with cherished drives together on Saturday mornings down Elston Avenue, veering past the looming Morton Salt warehouse, to junior classes at the Art Institute of Chicago, I was primed.

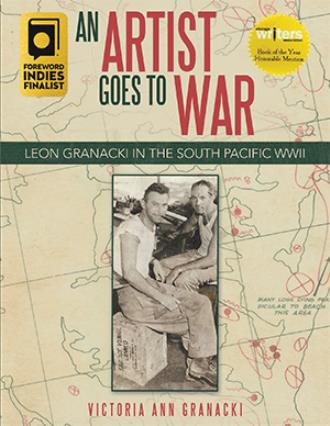

Those oil paintings looked so different from his other work, but I wouldn’t understand why until decades later. The scenes were from Bougainville Island in the South Pacific, where he served during World War II. He had been drafted into the US Army infantry many months before the US had ever declared war. He was 25 years old, out of high school almost 8 years, and well established in his commercial art career, but still single and ripe for Roosevelt’s pickings. With basic training under his belt by the time Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941, he was among the first troops to ship overseas.

Now it was 1953. Eight years after his discharge. Married and with 3 small kids, my parents had moved out of our cramped 4-room flat in a building packed with extended Granacki family at 1712 N. Washtenaw, and into an almost-as-old 3-flat on Keeler Avenue, still filled with extended Granacki family. Although he never spoke of his military service, that rough basement, out of sight, gave him room at last to sift through it all. He labored over a large scrapbook with a black leather cover and oversized 19 x 24” pages where he carefully masking-taped the corners of original watercolors – like the 2 he selected to create those oil paintings - as well as photos of his Army buddies at Camp Croft and Camp Forrest, flyers promoting Americal Division activities, and hand-drawn pen and ink maps of Japanese enemy positions during the Solomon Islands campaign. He’d sent this cherished collection home bit by bit with scores of wartime letters, and his older sister, Joy, lovingly saved it all. I don’t remember if I noticed him working on it at the time. Sadly, it was too late to ask him when, years later, I found it stored away in the bottom of a crooked basement cabinet.

Growing up in that 3-flat on Keeler, I was aware of a bulging brown binder of old letters sitting on a closet shelf in my tiny bedroom tucked under the stairs. Not sure when, but my Auntie Joy (whose family then lived on the second floor) had given my older cousin, Johnny, a project when he was home convalescing one year. He opened 196 wartime letters inscribed on multiple thin sheets, organized them by date, and stapled each letter onto a page in the binder. Most were written to “Dear Folks” in my dad’s flourishing script and were intended to be read by his whole extended family squeezed into the 6 flats of that Washtenaw apartment building.

The “folks” were married older siblings Al (Helen and 2 small children); Joy (John Rojewski and 2 small children); and Joe (Harriet and 1 son). His 2 younger brothers were Frankie, his best friend, confidant, and drinking buddy, and the youngest one, Rainer, known affectionately as Curly. Eighteen letters of the cache were in his grammar-school Polish and meant for the ears and hearts of his immigrant parents, Joseph and Victoria. Every once in a while, I’d peek into that binder and wonder what it was all about, but I never let on to him that I knew anything. And I was way too timid to ever ask.

My father died in 1993. The day after new tenants moved into his old flat, I got an excited call: “We’ve found something of your dad’s and I think you’ll want to see it right away.” I made a mad dash for Keeler, just a few miles down the street from my own home. As I burst in, they immediately handed me Most Secret: Memoirs from a Doughboy’s Past, the visual diary he began when he landed on Guadalcanal November 11, 1943. The precious little book had gotten shoved to the back end of the tallest shelf in my old bedroom closet. As I gingerly thumbed through the pages, I entered the life of my father the soldier – a life he kept most secret from all of us…..

He spent 4 years 1 month and 30 days in the US Army, being inducted as a private into the Illinois National Guard’s 33rd Division on April 14, 1941, and separating as a Master Sergeant from Fort Sheridan, Illinois on June 13, 1945. It was a journey of which I knew little, but now I had a treasure of written materials and visual images from his own artist’s hand that he’d painstakingly sent home. Other family members had saved and helped catalogue his story, augmented with their own letters back and forth updating his service. Now it was my turn, and I would chronicle it. I was about to embark on my journey through his life to understand how an artist became a soldier, and then a soldier became an artist again. This is the story of his journey – and mine.